The picture the Guardian ran, with the caption: Statistically, 85% of books are bought by women. Photograph: Alamy

Meredith Jaffe, writing in the Guardian (11/4/15), asks: “Middlebrow? What’s so shameful about writing a book and hoping it sells well?” Reading a recent essay in the Sydney Review of Books, she says, “it’s difficult to work out who its author, Beth Driscoll,

intended to insult the most: readers for liking middlebrow books, writers for having the temerity to write them, or publishers for bowing to the demons of commerce by printing them.

Throughout history, writers, musicians and artists have created works of art to keep the wolf from the door and satisfy their paymasters. Without that commercial imperative, there would be no Michelangelo, Mozart, Shakespeare or Dickens. What is so shameful about writing a book and hoping it sells well?

The answer is simple: nothing.”

The only probem being, Jaffe seems to have misread Driscoll, who’s writing more about marketing, about publishers trying to capture broader audiences for their respectable books. (Maybe the readers who respond to the market and get ensnared by books that are actually pretty good are the ones who should be insulted?)

(An aside: Ali Smith, at an appearance where she read from The Accidental, a novel at once wildly innovative and wildly readable, talked about the marketing department at her American publisher clarifying what sort of cover sells books–a girl, the color pink, and an item of clothing–though I’m sure given the time, I’d be able to turn these elements into a completely repulsive design.)

(An aside: Ali Smith, at an appearance where she read from The Accidental, a novel at once wildly innovative and wildly readable, talked about the marketing department at her American publisher clarifying what sort of cover sells books–a girl, the color pink, and an item of clothing–though I’m sure given the time, I’d be able to turn these elements into a completely repulsive design.)

Here’s Driscoll, in “Could Not Put It Down” in the Sydney Review of Books (10/20/15):

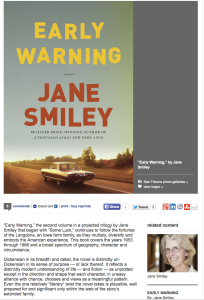

When publishers have a big new novel to promote, one with buzz and the potential for significant sales, they will often market it to women readers. These readers are the mainstream of literary culture: research shows that women are (and always have been) more likely than men to read novels, to attend writers’ festivals and to join book clubs. To attract these readers, a novel might be given a cover featuring images of women or children, it might come with a reading group guide, and it might be emblazoned with a sticker from another female-oriented media organisation: Oprah, Richard & Judy, or the Australian Women’s Weekly.

What effects might such packaging have on a novel’s critical reception? Despite recurrent proclamations of an end to cultural hierarchies, a move towards a broad readership still often means a move away from prestige. A book promoted in this way enters the terrain of the middlebrow, a word that suggests exclusion from serious literature.

In making her point, she describes the marketing and reception–and the quality–of three recent novels:

This is evident in three recent Australian novels, by Susan Johnson, Stephanie Bishop and Antonia Hayes. Each of these three novels has features that lend themselves to middlebrow readings, including their gendered packaging and their themes, particularly their attention to the ethics of intimate relationships. At the same time, other aspects of the novels, such as their formal techniques, work against the middlebrow and keep open the potential for these books to be drawn into literary circuits of reception.

She quotes a GoodReads comment:

Susan Johnson is an established author of literary fiction and non-fiction, with several of her books shortlisted for awards. The Landing is her breakthrough book, a change marked by its naturalistic cover image of a woman in a red dress standing at the edge of lapping water. It is not just critics but also readers who notice this packaging: as one wrote on the reader-review website Goodreads, ‘I am guessing that the marketing department at Allen & Unwin have chosen this cliché cover design to appeal to a wider audience than Susan Johnson’s readership who like her literary fiction.’

Jaffe and Driscoll are mostly in agreement, but they both should be put out by Ivor Indyk, whose piece, also in the Sydney Review of Books (“The Cult of the Middlebrow” (9/4/15)), Driscoll is actually responding to. In it Indyk decries the debasement of the “literary” as seen in the lowering of standards in prizes conferred upon books:

It’s in the giving of literary prizes that the cult of the middlebrow seems now to have established itself, which is quite a triumph, if you think of such prizes, as I still do, more and more desperately, as the last bastion, in this world, for the literary recognition that is withheld by the marketplace. I speak as a publisher, and so have to tread carefully – if I mention names I will be accused of bearing a grudge. I do bear a grudge actually – it’s about the thousands of dollars in entry fees I have to pay each year to support the administration of prizes that more and more frequently, in my view, go to authors who are neither challenging or innovative. What they do have, often in abundance, is ‘appeal’.

Which is rubbish. When books like Marlon James’s A Brief History of Seven Killings or Eimear McBride‘s novel, A Girl Is a Half-Formed Thing, or Eleanor Catton’s The Luminaries are winning top awards, it’s hard to see how one could say judges of literary prizes are overlooking “challenging or innovative” work (definitions that have had their own discussion lately).

Indyk thinks this is the fault of literary prize panels, who are going for the popular (and it may be true that the people behind the National Book Awards began a push a few years ago to make their prize-giving more relevant, as can be seen in the adding of a long-list as well as in the inclusion of much more accessible books on those lists ever since):

To whom, then, should we entrust the judgement of literary quality? I’m inclined to favour those who have a critical training in literature, a good knowledge of literary history, and a wide acquaintance with contemporary writing in all its genres. That would exclude a lot of writers, who might otherwise be chosen because they know the craft from the inside, or because they won the prize last time round. I don’t speak of the affiliations and rivalries to which writers might be subject, when judging the work of their fellows. The definition of critical competence I’ve given would seem to favour literary reviewers and literary academics. But many literary reviewers now are primarily writers; and those who are primarily reviewers will have already announced their likes and dislikes in advance, and in public, in their reviews. This must complicate their role as disinterested judges.

His solution?

So I am forced to the conclusion that no one is really suitable to be a judge of literary prizes.

(So such prizes should really be done away with–leaving the judging of worth to the forces of the market, again?)

Indyk, of course, is responding to an article in, well, the Guardian (8/31/15) by Jonathan Jones, “Get Real. Terry Pratchett is not a literary genius“, which measures the mourning for “mediocre” writers such as Terry Pratchett and Ray Bradbury, against the quieter public expressions of grief over the passing of writers of genuine brilliance, like Gabriel Garcia Marquez and Gunter Grass.

Jones in turn is taken to task, also in the Guardian (8/31/15) (Wow! Rapid turnaround!), by Sam Jordison, in a piece whose title says it all: “Terry Pratchett’s books are the opposite of ‘ordinary potboilers‘”

Ah, the humanity!

(An aside: Ali Smith, at an appearance where she read from The Accidental, a novel at once wildly innovative and wildly readable, talked about the marketing department at her American publisher clarifying what sort of cover sells books–a girl, the color pink, and an item of clothing–though I’m sure given the time, I’d be able to turn these elements into a completely repulsive design.)

(An aside: Ali Smith, at an appearance where she read from The Accidental, a novel at once wildly innovative and wildly readable, talked about the marketing department at her American publisher clarifying what sort of cover sells books–a girl, the color pink, and an item of clothing–though I’m sure given the time, I’d be able to turn these elements into a completely repulsive design.)